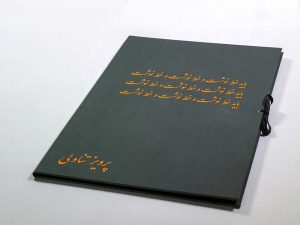

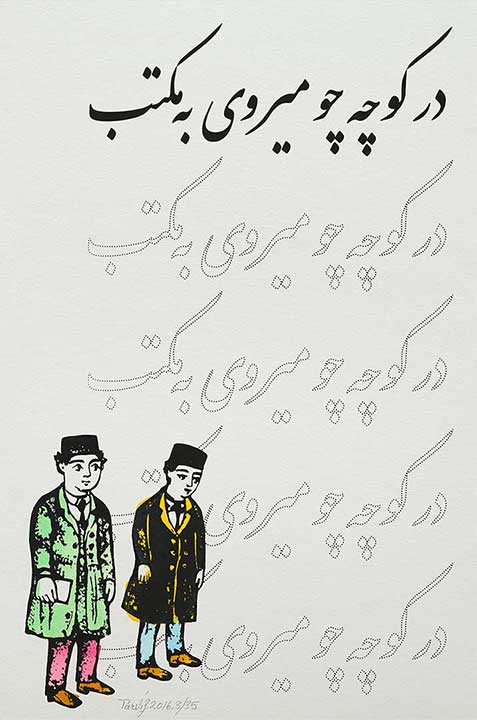

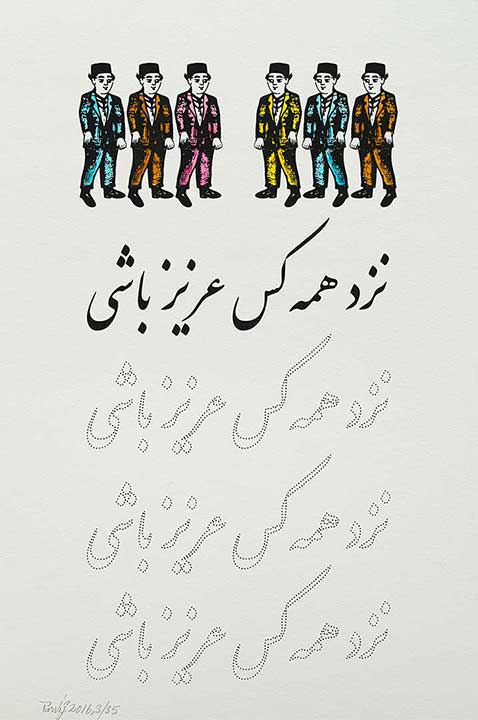

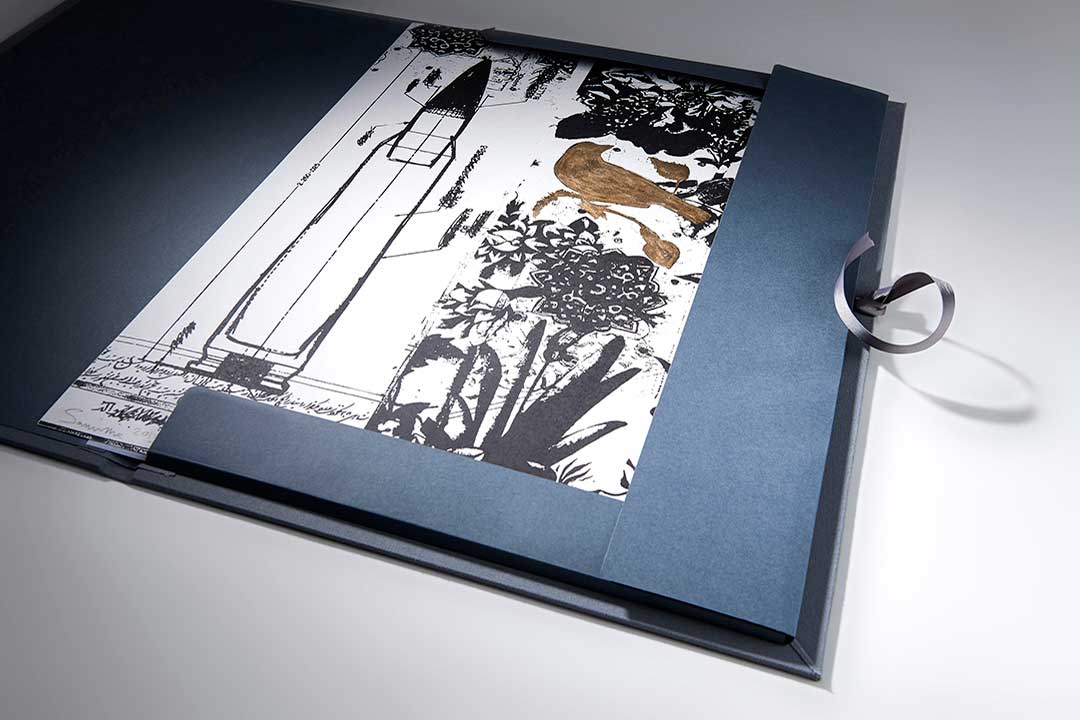

Exercise Writing

(2016)

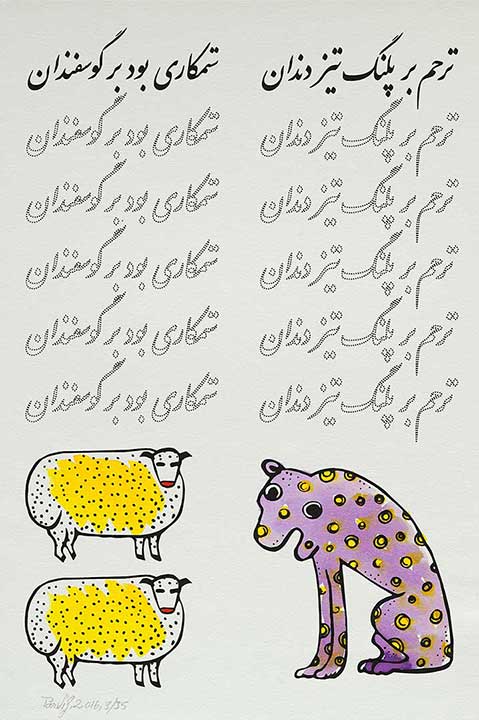

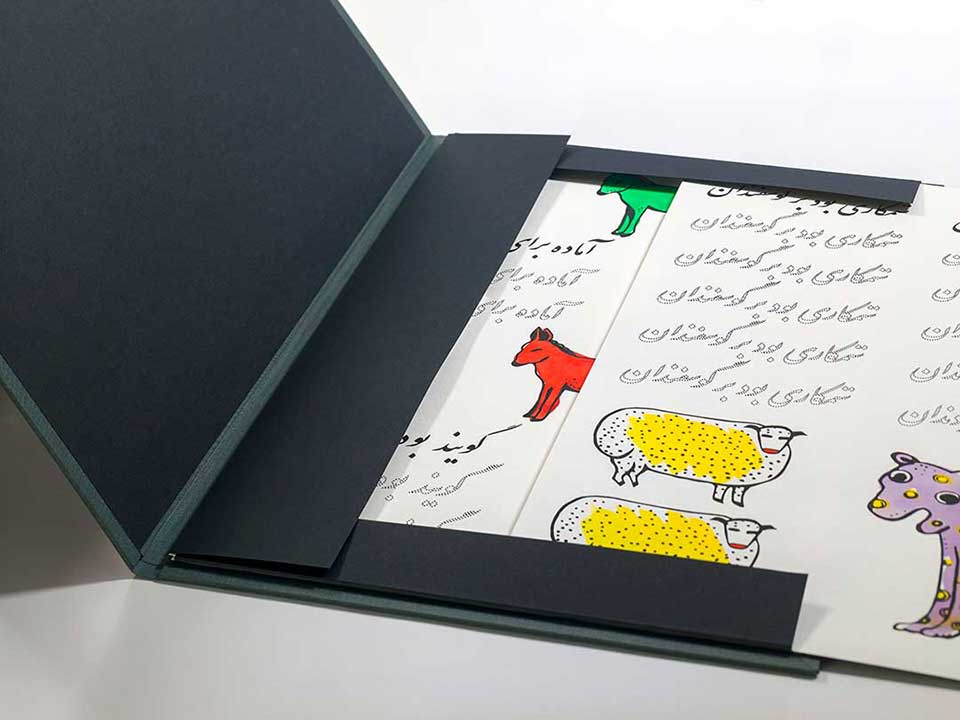

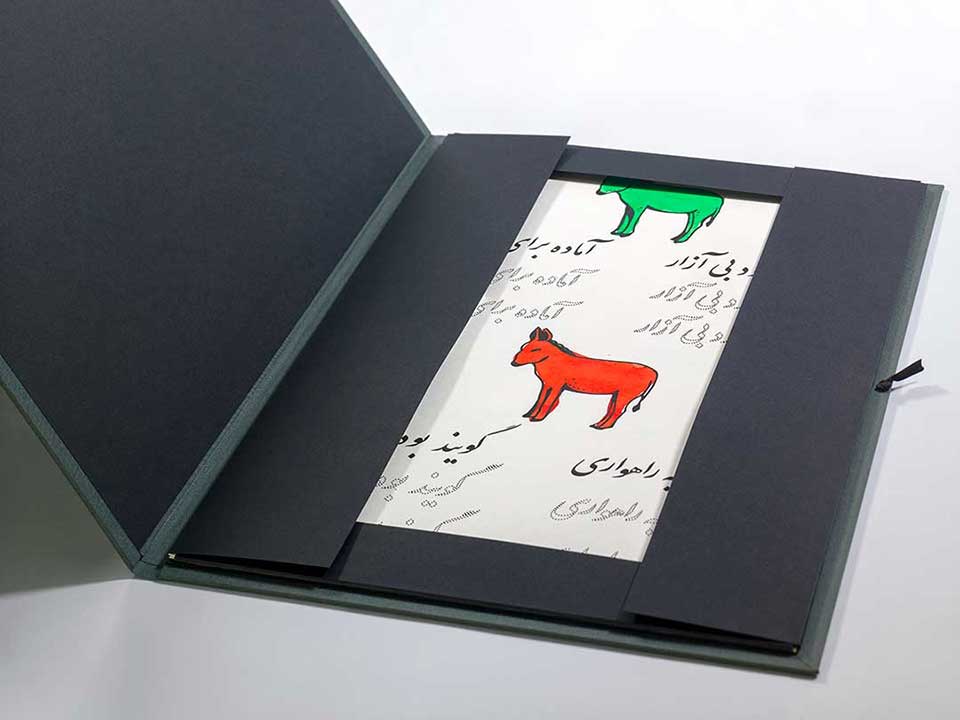

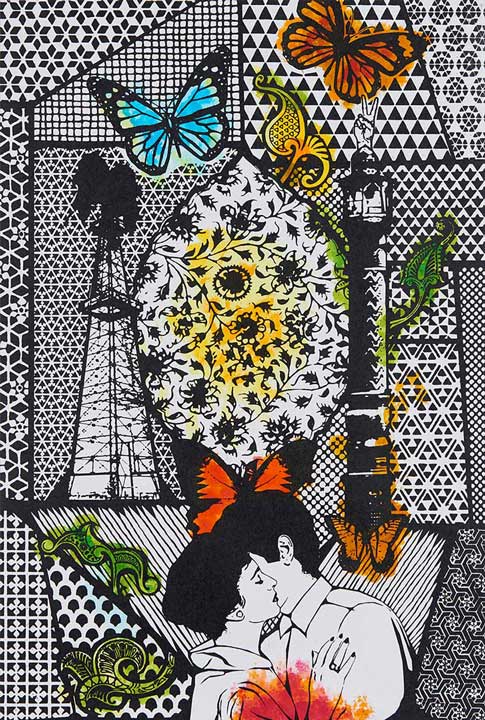

A suite of 5 original hand-coloured screen prints

Edition of 35 and 5 Artist’s Proofs

Collection: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

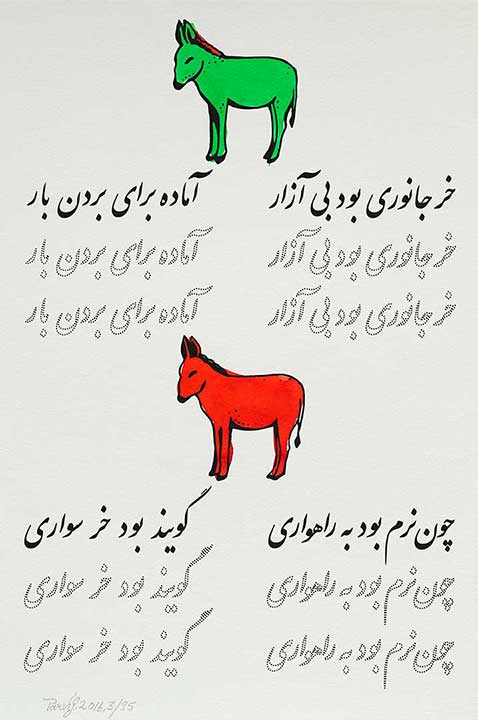

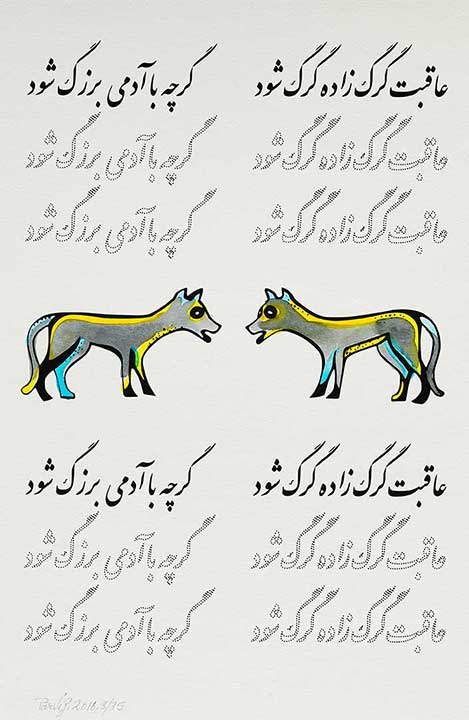

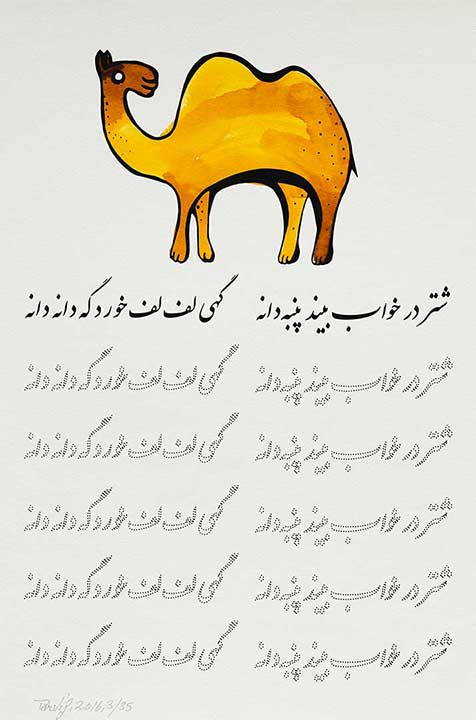

“My entire childhood and adolescence was about manners. In addition to home, I was required to be polite and clean at school too. The assistant principal spoke in praise of manners every morning and the calligraphy teacher asked us to repeat lines commending manners. But outside home and school it was very different. No one else was as clean as we were. On the streets we sometimes ran into men who used dirty words to call each other’s mothers and sisters, suggesting intimate relations with them. I have never forgotten some of those scenes from life back then.” Parviz Tanavoli

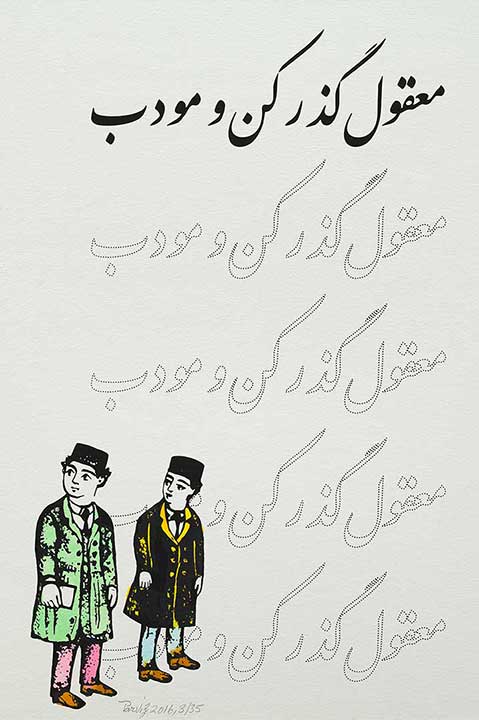

In the early 1960s Parviz Tanavoli created a collection of which only a few images have been published before. In this collection, different from his other works, he created a writing board like those used in grade school to teach penmanship, and on top in elegant Nasta’liq calligraphy wrote a line, which he then repeated in dashed lines below. What made this work avant-garde at the time and set it apart from the art of its time was Tanavoli’s conceptual approach to the canvas. There is no sign of calligraphy-paintings in this series, and no sign of figures and imagery. It doesn’t even have any colors. What the viewer sees is a line of writing and the dashed lines running the length of the canvas below.

In his selection of the written line Tanavoli cleverly placed the viewer in the same position he has had in society throughout childhood and adulthood. In Iranian society and social-political history people have permanently been in the position of being advised: the king is always a shepherd and the masses the flock.[i]

Tanavoli recalls, “All I remember from school is being advised to be clean, polite, and to study. But the person giving the advice never met his own responsibilities. They inspected our uniforms every morning to make sure they were clean and free of spots, without bothering to clean the streets and the town square. And without the government meeting the minimum standards of public health in the school or throughout the city.”[ii]

Based on the series mentioned above and using images from it Parviz Tanavoli has created two collections of hand-colored Screen-prints, which are reminiscent of the schoolbooks from his youth. The collections “Manners” and “Exercise Writing” are based on what he created fifty years ago, like the writing boards given to children to teach them writing and manners through the repetition of phrases and poems.

Tarlan Rafiee

i: A line of poetry from the Bustan of Saadi.

ii: Interview with Parviz Tanavoli by Tarlan Rafiee, Winter 2015.

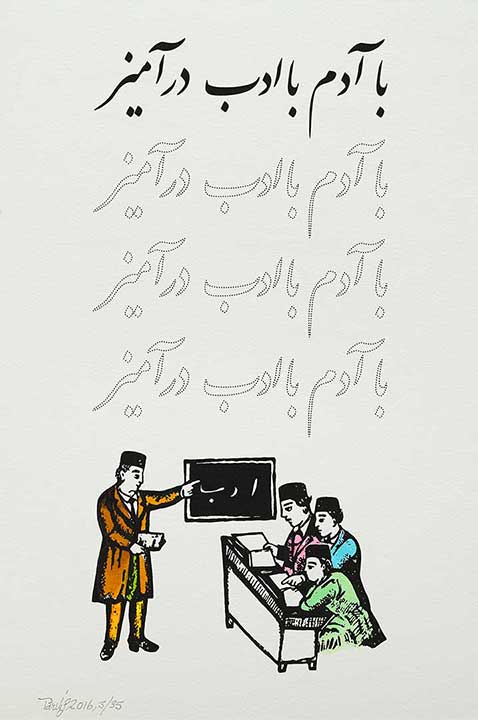

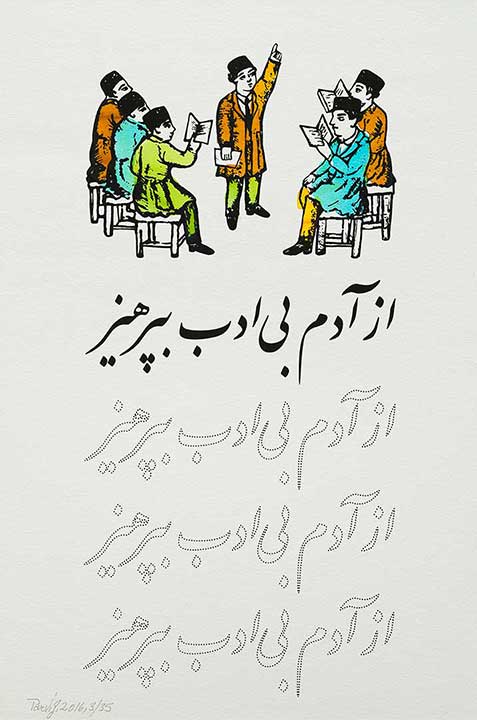

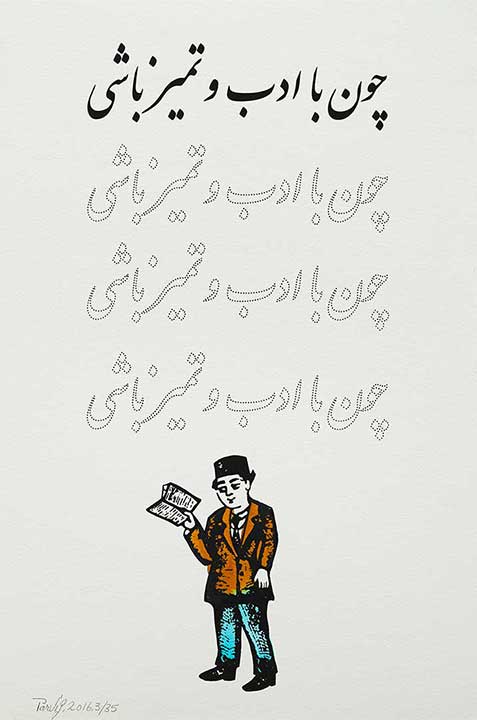

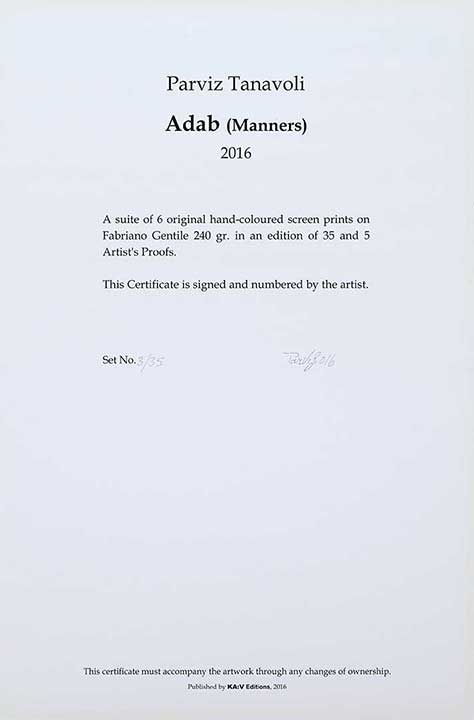

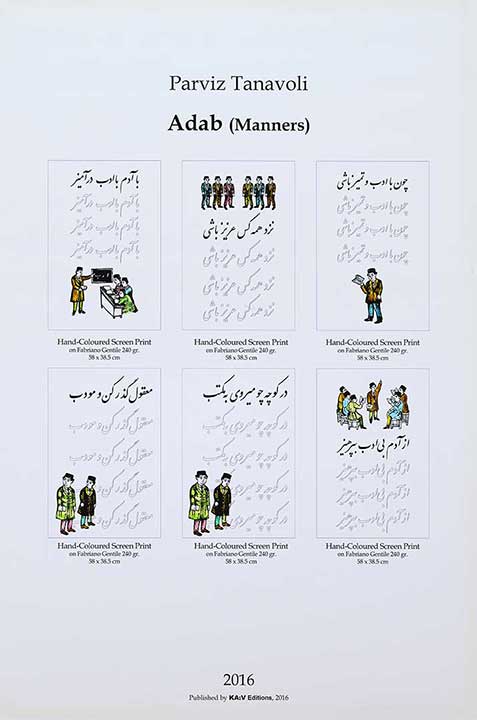

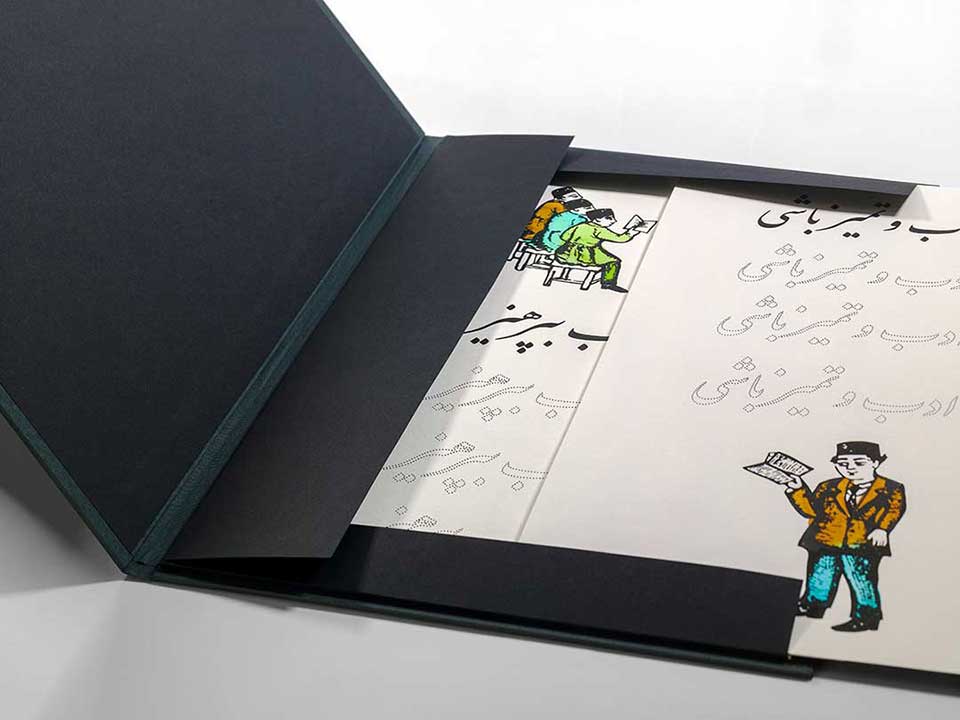

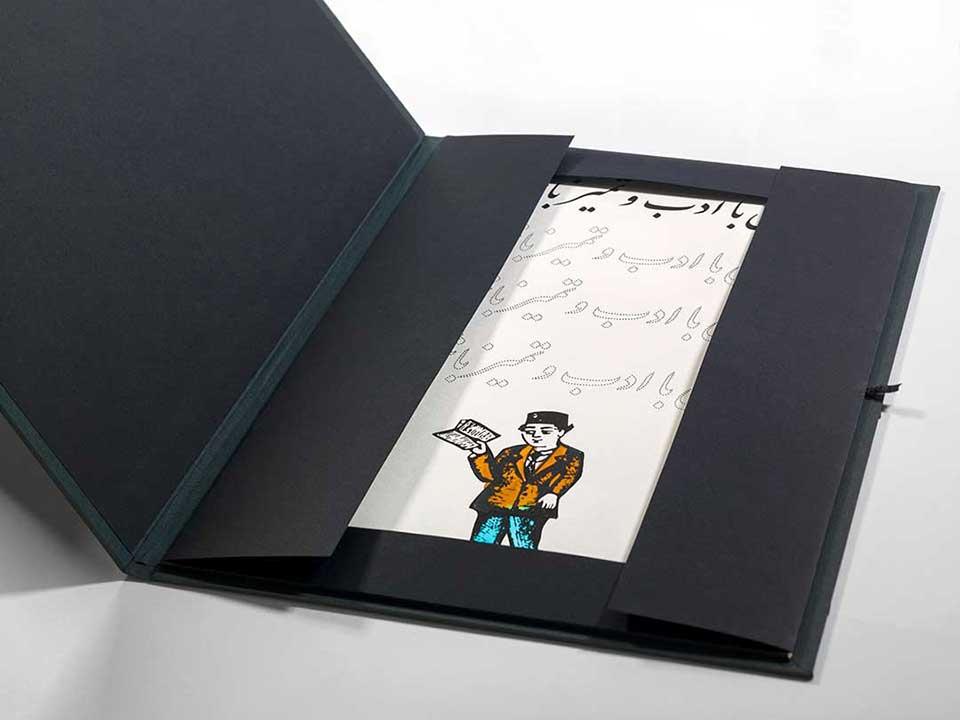

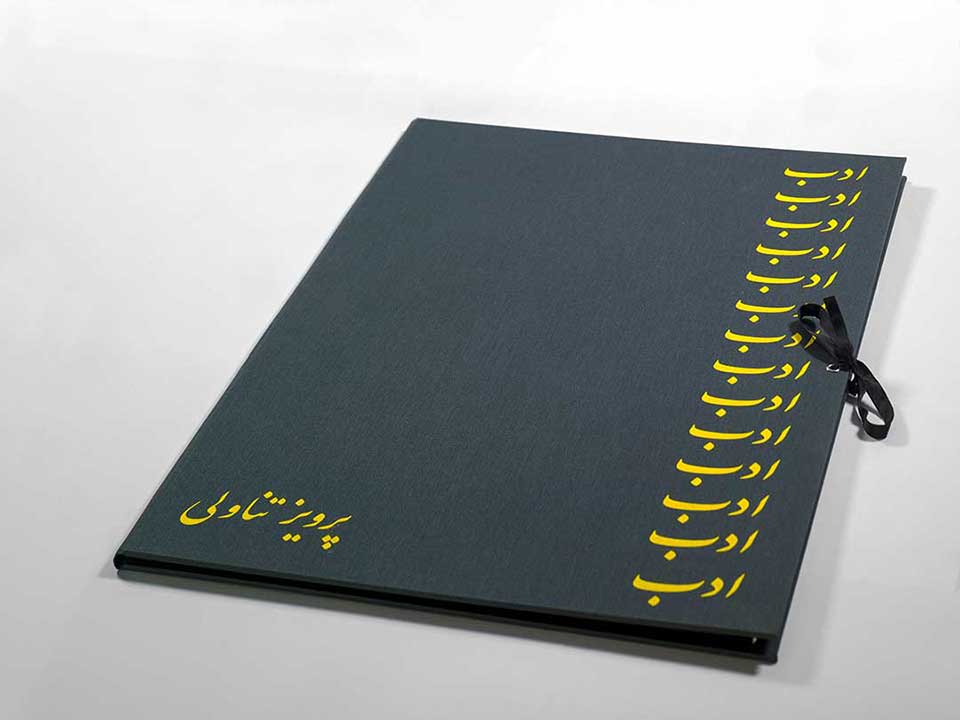

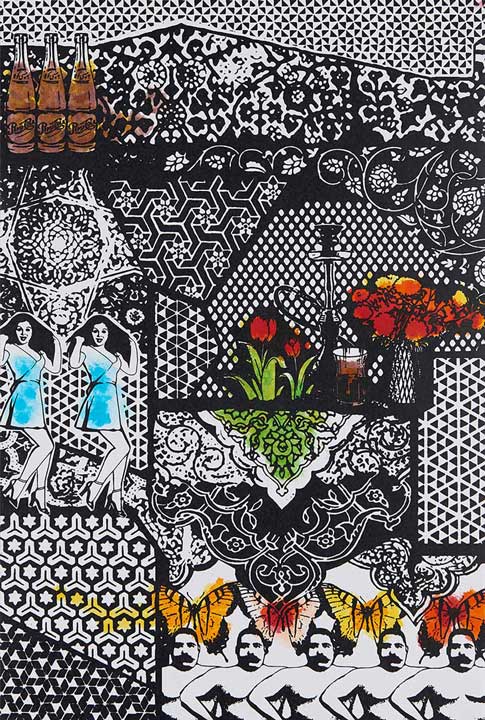

Adab

(2016)

A suite of 6 original hand-coloured screen prints

Edition of 35 and 5 Artist’s Proofs

Collection: The British Museum

Collection: The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

“My entire childhood and adolescence was about manners. In addition to home, I was required to be polite and clean at school too. The assistant principal spoke in praise of manners every morning and the calligraphy teacher asked us to repeat lines commending manners. But outside home and school it was very different. No one else was as clean as we were. On the streets we sometimes ran into men who used dirty words to call each other’s mothers and sisters, suggesting intimate relations with them. I have never forgotten some of those scenes from life back then.” Parviz Tanavoli

In the early 1960s Parviz Tanavoli created a collection of which only a few images have been published before. In this collection, different from his other works, he created a writing board like those used in grade school to teach penmanship, and on top in elegant Nasta’liq calligraphy wrote a line, which he then repeated in dashed lines below. What made this work avant-garde at the time and set it apart from the art of its time was Tanavoli’s conceptual approach to the canvas. There is no sign of calligraphy-paintings in this series, and no sign of figures and imagery. It doesn’t even have any colors. What the viewer sees is a line of writing and the dashed lines running the length of the canvas below.

In his selection of the written line Tanavoli cleverly placed the viewer in the same position he has had in society throughout childhood and adulthood. In Iranian society and social-political history people have permanently been in the position of being advised: the king is always a shepherd and the masses the flock.[i]

Tanavoli recalls, “All I remember from school is being advised to be clean, polite, and to study. But the person giving the advice never met his own responsibilities. They inspected our uniforms every morning to make sure they were clean and free of spots, without bothering to clean the streets and the town square. And without the government meeting the minimum standards of public health in the school or throughout the city.”[ii]

Based on the series mentioned above and using images from it Parviz Tanavoli has created two collections of hand-colored Screen-prints, which are reminiscent of the schoolbooks from his youth. The collections “Manners” and “Exercise Writing” are based on what he created fifty years ago, like the writing boards given to children to teach them writing and manners through the repetition of phrases and poems.

Tarlan Rafiee

i: A line of poetry from the Bustan of Saadi.

ii: Interview with Parviz Tanavoli by Tarlan Rafiee, Winter 2015.

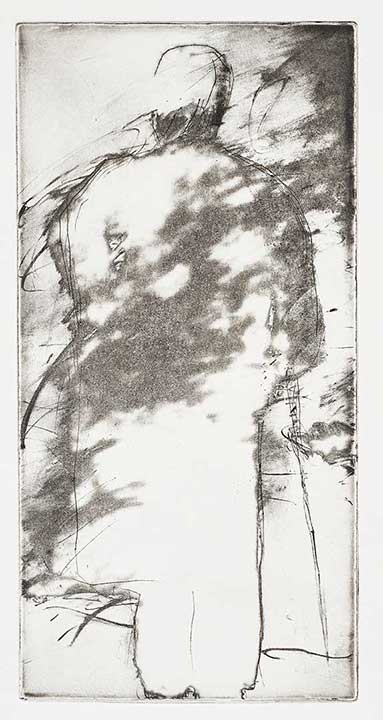

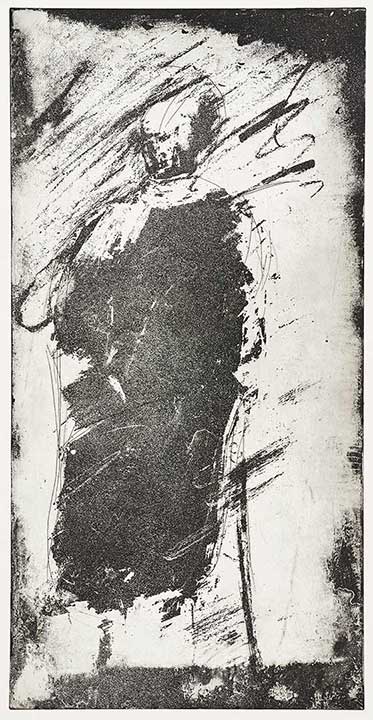

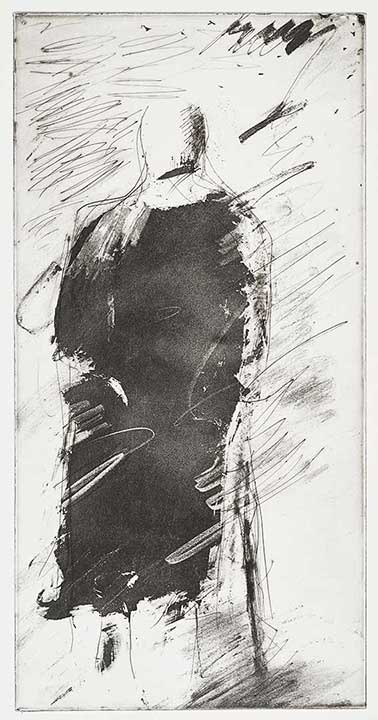

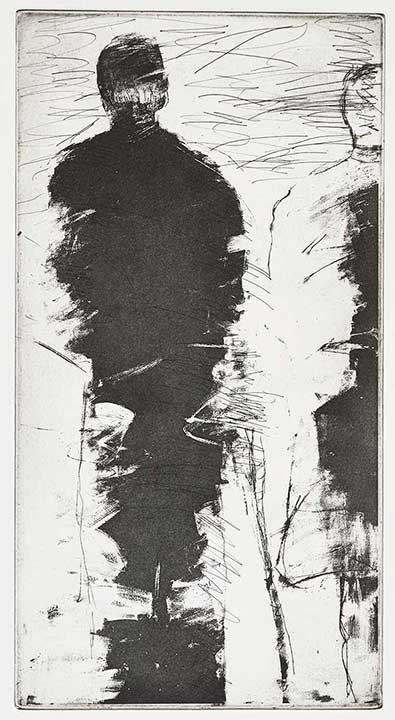

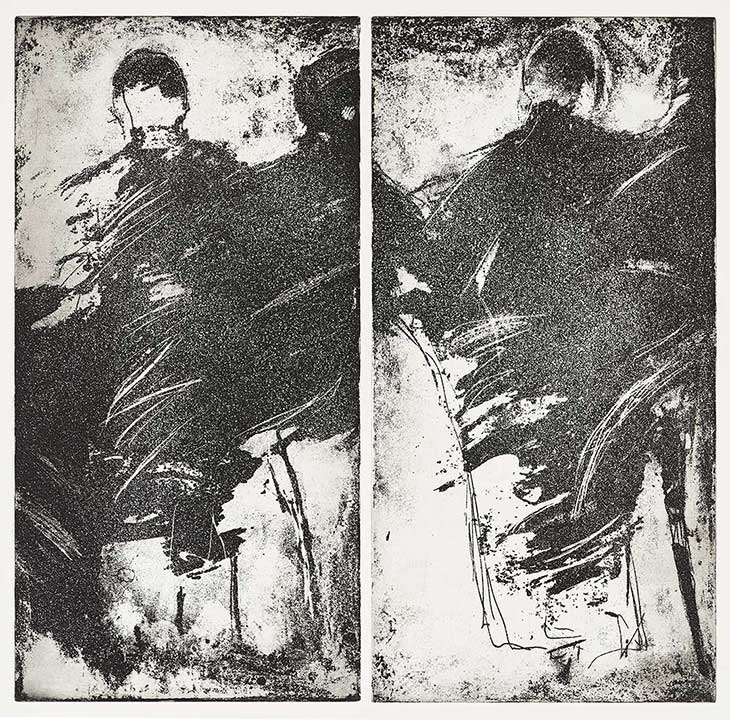

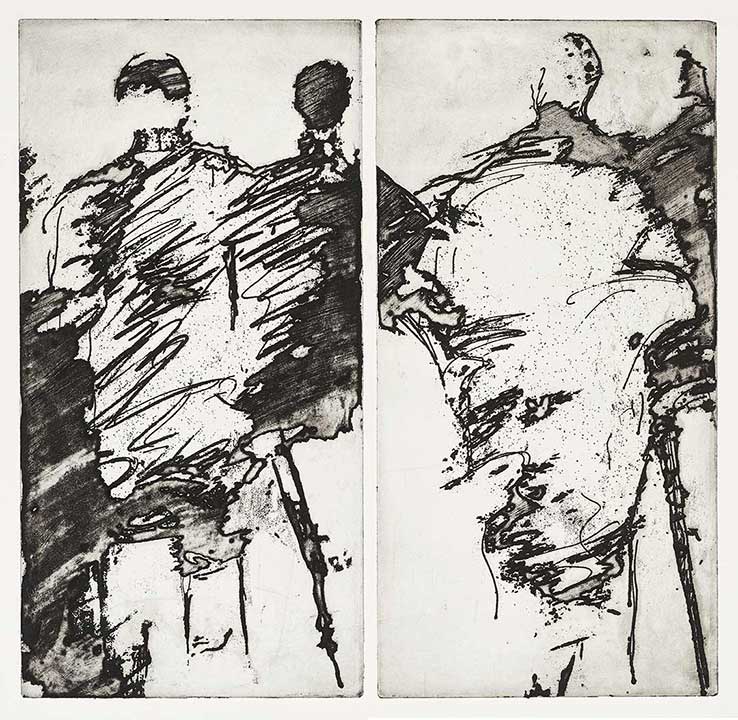

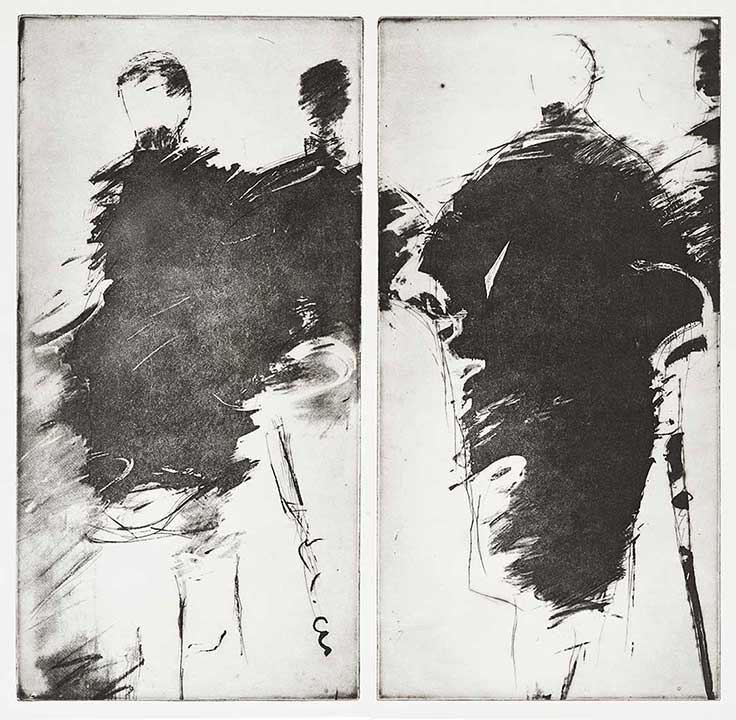

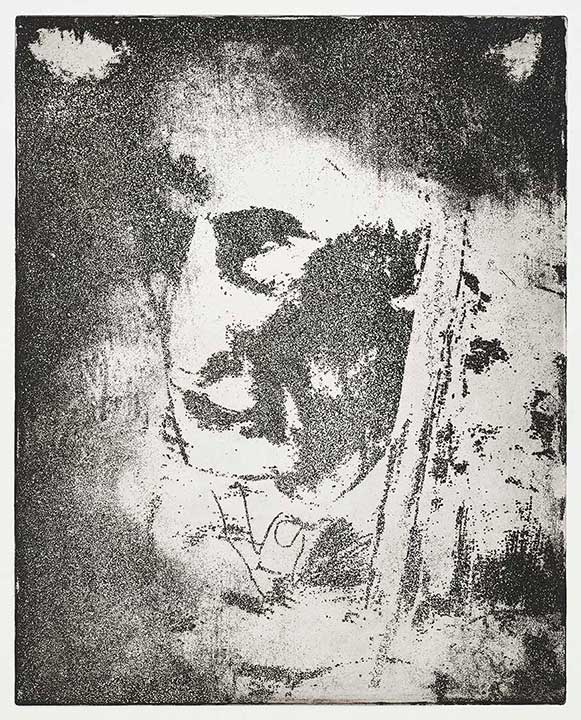

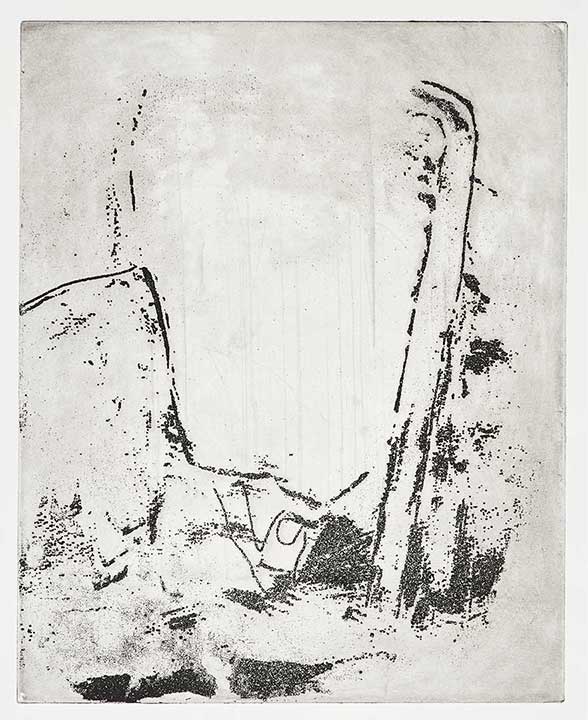

Mossadegh

(2012 – 2013)

Photo-Etching, Etching, Aquatint and Drypoint on Paper

Collection: The British Museum

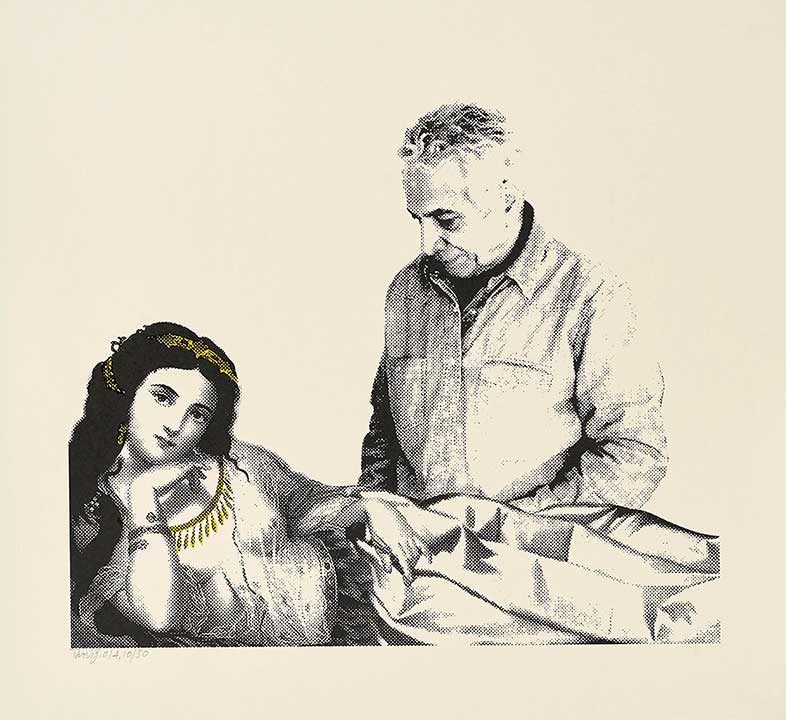

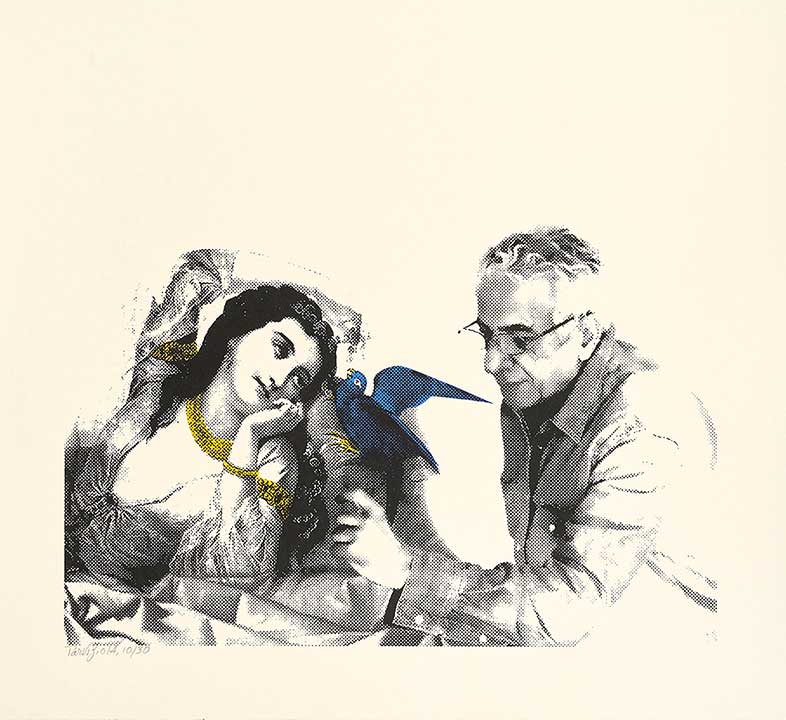

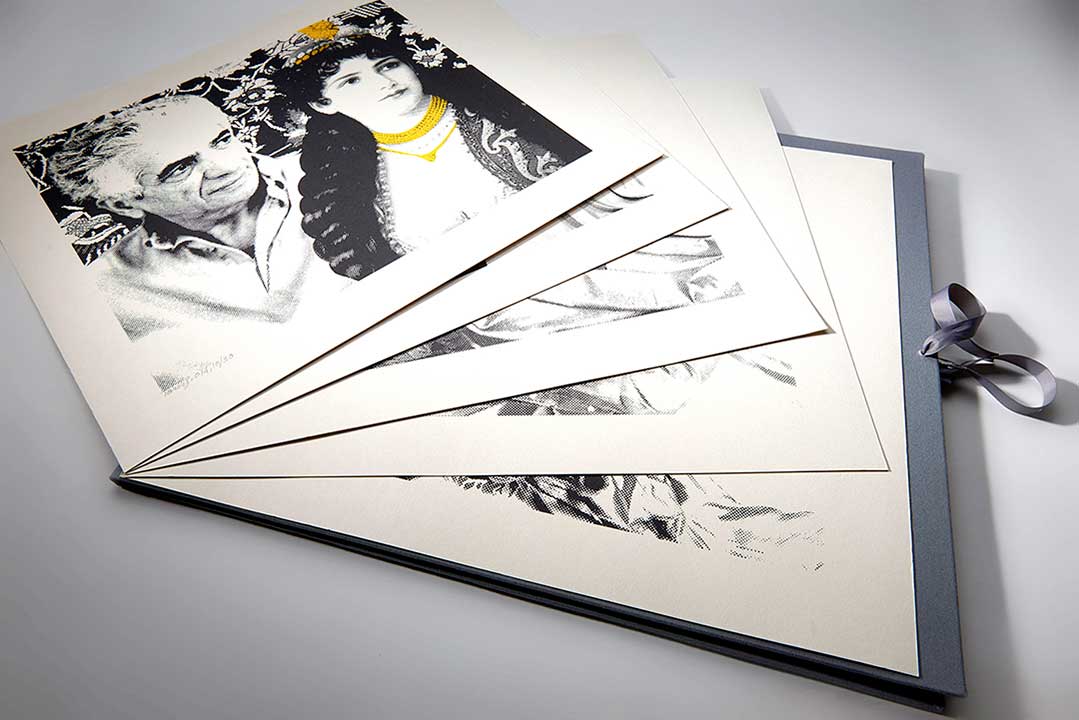

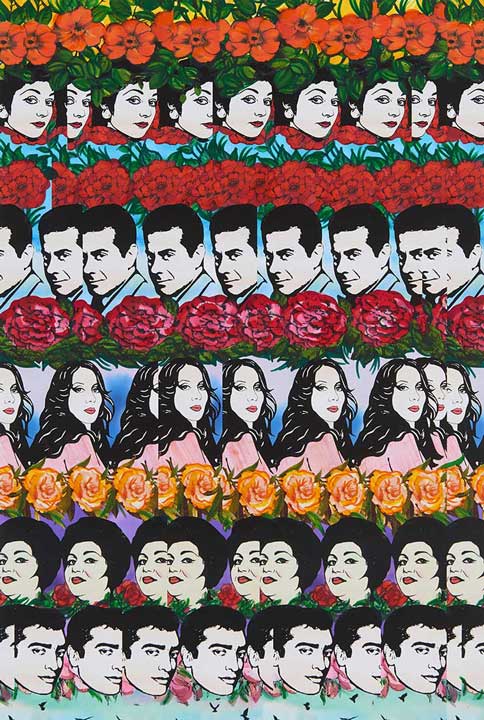

Farangi Women & Me

(2014)

A suite of 5 original screen prints in an edition of 30 and 5 Artist’s Proofs.

Shown at The British Museum, Aga Khan Museum

Collection: The British Museum

“During the course of the 19th century a relatively modern medium entered the private space of Isfahan houses and became a popular feature of interior design in Qajar Iran. This was print media – lithographed images on paper and postcards – and their subject was European women. The Persian word ‘Farangi’ for Europeans is a corruption of the word Frankish’, because among the earliest European travellers to Iran were Frenchmen, and for Persians that word came to represent all Europeans, from whatever country.”

“By the 19th century, such images became available more cheaply as mass media, as imported prints or newspaper illustrations, and they were enthusiastically received. They were displayed in homes, fixed to the walls and the ceilings, for the entertainment of family and friends. This was a fashion trend which was apparently enjoyed throughout the country, and for the entire Qajar period. “

“The love of the Isfahanis for these images created an aura of excitement and brought new life to their homes. In those days, it was brave to keep images of partly naked women and expose them to family and the guests. The risk of being condemned for breaking religious rules and for being blasphemous was high. Yet the Isfahanis managed to avoid trouble. “

“Another courageous action of the Isfahanis was their brave decision to mix a Western medium and a Western subject with traditional Iranian art forms such as mirror works and floral-decorated stucco.”

(European Women in Persian Houses. By Parviz Tanavoli. I.B.TAURIS 2015)

In fact the Art of Qajar era, formed on the fundaments of Safavid High-Art and European Middlebrow. The European hegemony changed the taste of the courts of Qajar aristocrats, Soon spread to the ordinary people’s life. These new decorative elements placed on Porcelains, tiles, textiles, rugs; Even in iconic religious paintings and reliefs, the faces and the figures of these Farangi women replaced the traditional figures of angels.

Parviz Tanavoli, as a researcher, has tracked some of the most famous of these lithographs and prints through various medias over decades. According to his researches very few of these images used and copied thousands of times repeatedly on rugs, murals, paintings, tiles etc. for over a century. Some of them are still being copied and used as lowbrow art such as posters, postcards and cheap ceramic works.

He believes that these images of women, following the westernization of the society, played an important role in making a new era in Iranian art history. The presence of women in society challenges patriarchal power of traditions; bringing women to the foreground, changing the dominant role of men in traditional society, changes of clothing, behaviours and traditions are what women are still fighting for. Tanavoli, as a researcher, has been always looked at these images like the pieces of a bigger puzzle in modernization of his country.

Parviz Tanavoli, after decades of following, tracking and searching for these “Farangi Women”, now standing side by side of them, admiring them, telling stories for them, reading poems for them and showing us some fragments of his life spending with them. His self-portraits with these guests to our houses, on our rugs and carpets, and our paintings for over a century, are the most poetic story from him.

This portfolio of prints, “Farangi Women & Me”, limited to 35 editions and 5 Artist’s Proofs, produced in Tehran by KA:V Editions in 2014.

Yashar Samimi Mofakham

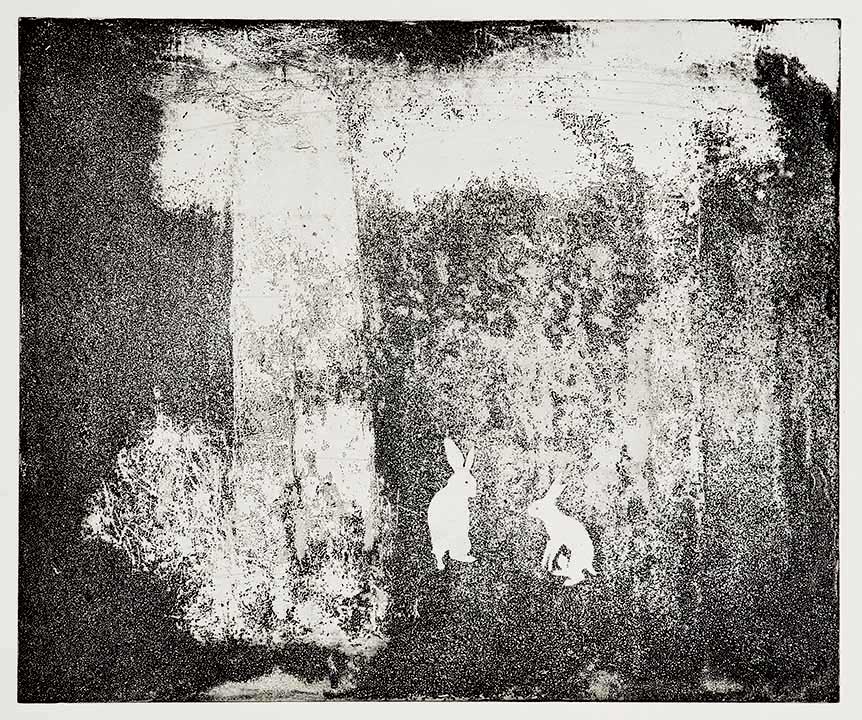

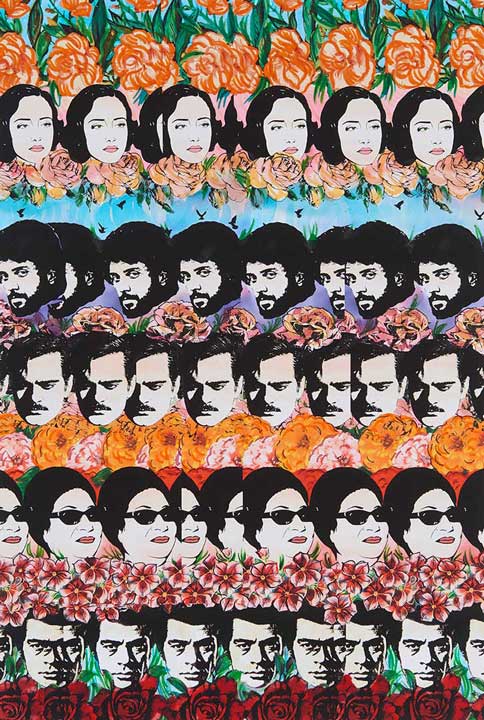

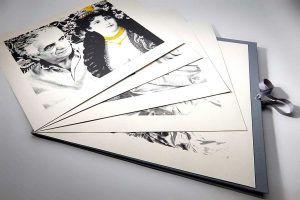

30 Years

(2015)

A portfolio of 10 Unique-multiple prints in an edition of 10 and 2 Artist’s Proofs

First launched at JAMM Art Gallery, Dubai

Shown at The British Museum

Collection: The British Museum

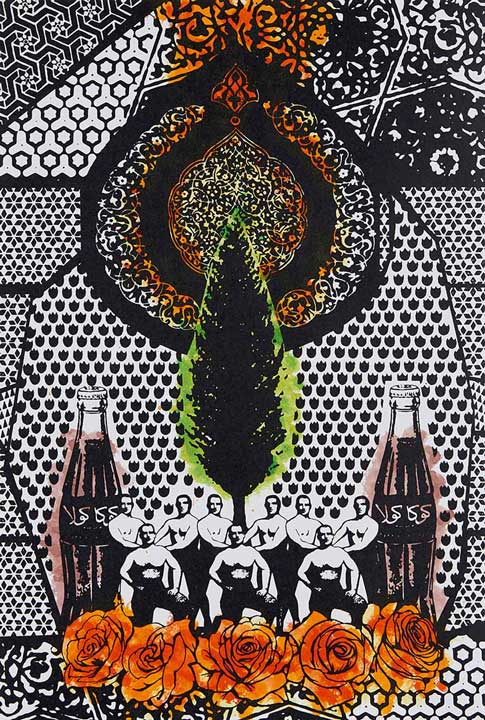

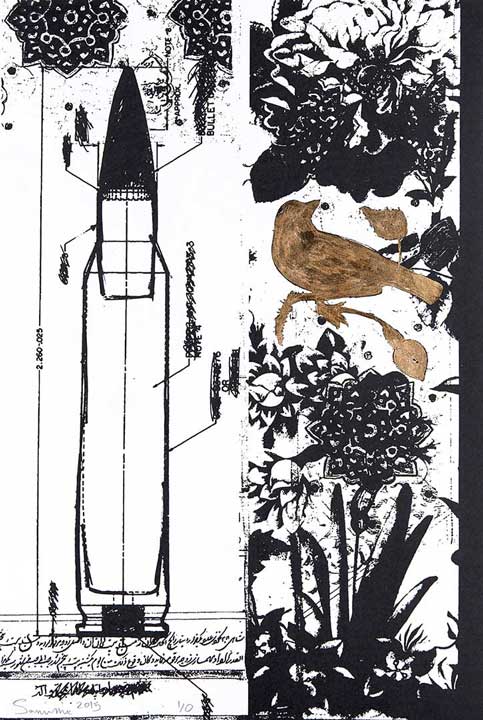

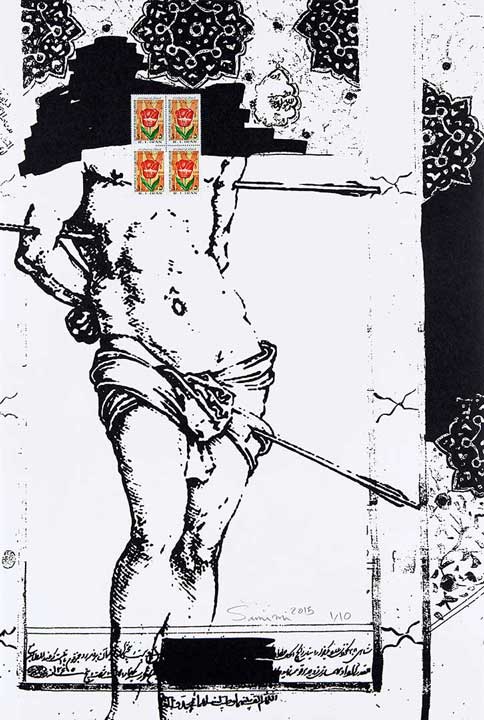

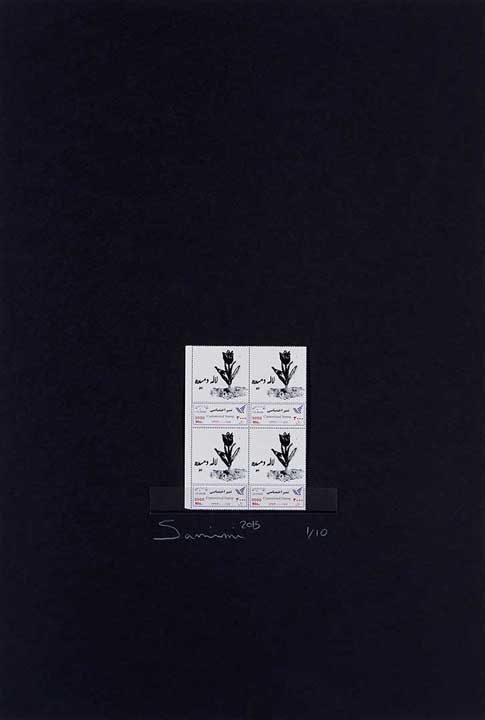

Tarlan Rafiee’s and Yashar Samimi Mofakham’s works complement each other in their quest for truth behind the violence, propaganda and patriarchy that exist in this part of the world.

In her hand-coloured prints, Rafiee depicts Middle Eastern divas, pop singers, actors and actresses in order to remind us that the region has a cultural dimension that is far removed from the cliché of the region as a land of oil and the internal/external strife that arise from that. The Middle East is also home to various ethnic groups with a rich culture and centuries-old traditions. The personalities depicted by Rafiee such as Googoosh, Fairuz, Omar Sharif and Umm Kulthum have acted as ambassadors for Middle Eastern culture in the wider world and have also helped advance their respective societies.

In his silkscreen prints, Samimi Mofakham references a number of iconic works in art history such as the Venus de Milo and Dürer’s Saint Sebastian at the Column. The former was utilised by the French as a tool of propaganda to argue its artistic superiority to Medici Venus, after they had returned it to Italy. In Samimi Mofakham’s rendition, this classical symbol of feminine beauty is beheaded and her breasts are censored with Iranian stamps celebrating the anniversary of the Revolution, which resonates with the current status of women in Iranian and Arab societies. The martyr Saint Sebastian symbolises all the young men who died in the war and how those deaths were used as a tool for manipulation by the regime’s propaganda machine.

Having endured revolution, war and multiple social movements in their young lives, the works of Samimi Mofakham and Rafiee reflect a fragment of their own experiences and serve as mirrors of their external realities.

The portfolio comprises two giclée prints, hand-coloured with gouache, ink and pencil, six silkscreen prints with gold leaf and old Iranian stamps and two collages made with personalised stamps.